30 April 2006 in Tokyo

TAKEDA Ken-ichi + ARAI Shin-ichi (Japan)

"Tourist #8 International"

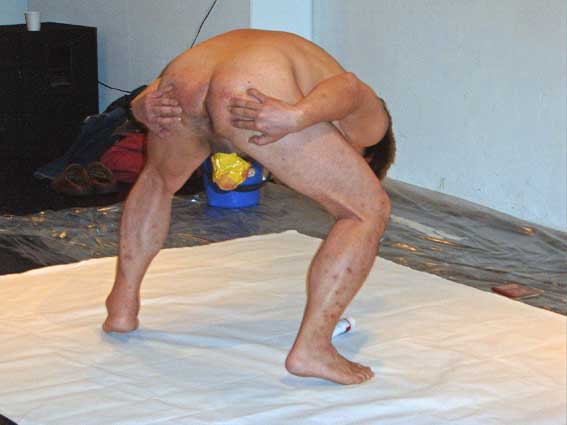

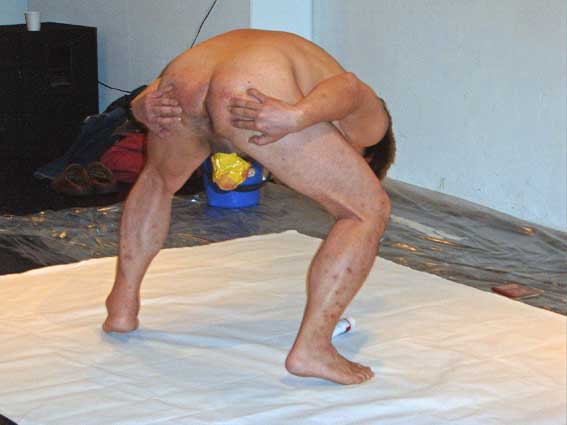

ARAI shows his ass hole

ARAI sing a national anthem of Japan "Kimi ga yo"

"May the Emperor's rule last

Till a thousand years, then eight thousand years to come

Till sand, pebbles, and rocks

To be united as a ledge

Till moss grows on it"

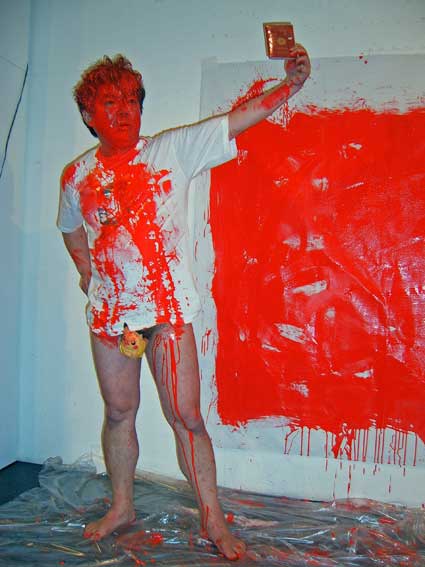

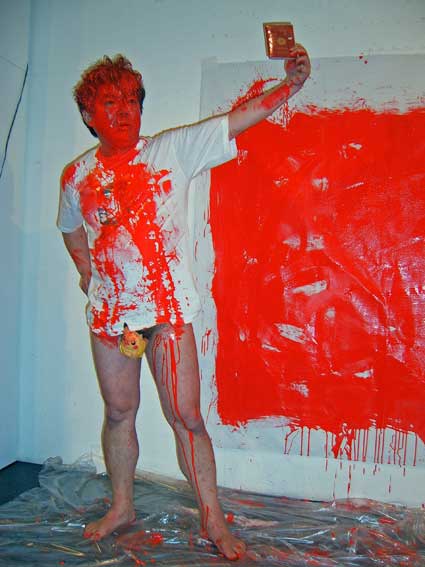

ARAI sing "The Internationale" in Japanese. (right TAKEDA Ken-ichi)

"So comrades, come rally

And the last fight let us face

The Internationale unites the human race.

So comrades, come rally

And the last fight let us face

The Internationale unites the human race. "

Words by Eugene Pottier (Paris 1871)

Music by Pierre Degeyter (1888)

again ARAI sing "The Internationale" in Japanese

ARAI and Japanese pasport using similar emblem of the Imperial crest of

the chrysanthemum.

Social Tensions: ARAI Shin-ichi

CREATIVITY AND ABJECT NATIONALISM

by Berenice Angremy

("Art AsiaPacific" Spring 2004, No.40)

ARAI Shin-ichi is an established Japanese performance artist who has been working around the world since the 1980s, especially in Asia and Western Europe. His performances are direct, clear and obvious -- perhaps too obvious at first glance.

Strongly influenced by an earlier generation of politically minded postwar Japanese artists associated with the Gutai movement in Osaka and Neo-DADA-organizers in Tokyo in the 1950s and 60s, Arai's actions and performances denounce nationalism and identity obsession.

Recently, at the 4th Open Art Festival which took place in Changchun, China, September 2003, Arai performed "Happy Japan!," a well known performance work which is his signature piece having been performed more than ten times since 1999.

For the performance, Arai dressed soberly in a dark green suit which, he tells us, is the uniform of Japan Overseas Cooperate Volunteers,

a body of young people under 40 to propagate Japanese civilization around the world. And the honorary president of the Organization is

the Emperor.

In a clear, unemotional speech, he introduces his audience to the book he holds in his hands, "War theory," a controversial comic book that has sold a most a million copies.

It looks like an ordinary, inoffensive comic book but is in fact a compendium of ultranationalist propaganda, featuring revisionist theses about tragedies of modern Japanese history-denying, for instance, the Nanjing genocide in China as well as the sexual slavery imposed on Southeast Asian women by the occupying Japanese army during the Second World War.

He then takes off his clothes, keeping only a small yellow "Pikachu Pokemon" fig leaf on his genitals, and squats on a square white canvas on the floor. While singing the Japanese national anthem, he presses a plastic tube of Riquitex containing red paint from just below his buttocks, as if excreting red human waste.

Using his bare buttocks on the "waste," he paints a full but irregular rising sun in the middle of the white canvas that turns out to be a copy of the Japanese national flag, which he later hangs on the wall.

He then tears out random pages of the comic book, giving some to the audience, and stuffing others into his mouth after reading out a few lines. He chews them, shouting "Happy Japan." At the same time, the accumulation of paper in his mouth blocks his emotional speech, making his voice hoarse before it disappears entirely inside his throat.

The performance ends when a last, almost inaudible "Happy Japan" emerges from his suffocating mouth, while tears run down his pain-distorted face.

Is Arai an activist -- which is how he is often perceived in Japan outside performance art circles? Is he really an artist -- which is how he is received abroad, especially in China where his performances always move his audiences deeply? The emotion prompted by his work is on multiple and successive levels, and reveals that his performance is subtler than it seems:

it goes beyond the simple eruption of anger and rage provoked by ultra nationalism, slowly assuming innocuous form.

This is also the case of his other performance pieces -- such as the Tourist's Series, the last episode of which, "Tourist #7 Viva Globalism!," was also performed in Changchun:

a performance with a crude political message, so banal and comic that it may lull the audience into cynicism, is suddenly disturbed by scenes of painful incorporation, the multiple waves of intense emotions produced progressively engulfed its audience; herein lives the force of Arai's work. His criticism is based on images which despite looking like childish artifacts, reveal terrifying techniques of mass production and consumerism:

the Pokemon figures (Pikachu as a fig leaf) which feed the imagination of children the world over; and the Manga images which are present everyday in the life of Japanese people and in the art scene (MURAKAMI Takashi) and beyond, forge the image that Westerners have of contemporary Japanese art.

"Here in Japan, which is said to be rich, to be a mature democracy, to have freedom of expression, all I can do is just cry," Arai said in a recent interview. All societies which have experienced wars of aggression go through revisionist phases to deal with their feelings of guilt and to deny their collective responsibility -- and thus commit another crime, that of denying the humane essence of their victims and their right to memory and justice.

When a publishing house transforms its revisionist ideology into a social phenomenon, with the commercial success of a book (War theory) at least in part due to its popular Manga form, the sense of unease goes even deeper.

Arai doesn't use his body to express his political rebellion in a theatrical fashion, by miming or acting it out -- he lives it. He makes his body experience his political conscience by eating the

source of nationalism and defecating the symbols of the Japanese nation.

Moreover, his body in action creating the image of the Japanese flag

takes him even further from the traditional anti-establishment gesture:

the burning or shredding of the national flag. Action is not based on destruction, or indirect use but on simple, straightforward creation.

In other performances, he insists on performing

along with "Happy Japan!" at festivals, Arai follows the same process:

a narrative discourse, followed by action -- first, comical, then intense or even dramatic.

All his recent performances in China -- "Tourist #4 Globalism/lnternationalism", "Tourist #6 You're no good" and "Tourist #7 Viva Globalism" denounce excess consumerism. The body in action becomes a focus for social tensions to manifest themselves and attitude becomes form.

His performances can sometimes disturb his audience -- either because of the issues he raises or simply because of the taboo, intimate presence of his own body, naked or clothed.

Yet, the body of Arai is not on show (a show -- a theatrical performance -- is easier for an audience to assimilate), it isn't a tool in the service of art -- it is art at the moment of performance.

In this way, the work of Arai links up with the most radical expressions of performance art from its beginnings in the 1950s -- the Gutai Group and Neo-DADA-organizers in Japan, the Viennese Actionists in Austria, and Body Art in the U.S.

In Asia, performance art first developed in Japan, in an atmosphere conducive to the emergence of counter-culture ideals similar to the ones present in Europe and America. The famous Gutai group founded in 1955 in Osaka by YOSHIHARA Jiro, and the Neo-DADA-Organizers in Tokyo, set the tone:

a radical, physical art of expression which would occasionally manifest itself as a political response to the desolation of post-war, post-Hiroshima Japan.

The isolated actions of artists such as SHIMODA Seiji in the 1980s, while set in a context of social and political protest, were also accompanied by touches of theatre and poetry which gave performance art a personal dimension and a formalist aesthetic. The contemporary performance art scene in Japan undoubtedly owes much to the irrepressible energy of Shimoda, who ever since the creation of the Nippon International Performance Art Festival (NIPAF) in 1993, has inspired and gathered together performers mainly from Japan and Asia.

In this context open to all forms of performance art, artists like Arai have been able to give free rein to their libertarian, challenging and creative acts.

Arai's artistic language is undoubtedly a fundamental part of his own country's contemporary art scene -- in that his political opposition, mainly aimed at issues of globalism and nationalism, experienced with humour and insight (despite and we should say because of its obviousness) precedes the expression of his personal experiences and the aesthetic dimension of his performances. Although less poetic and formalist than many other performers in NIPAF.

Arai forces us by virtue of his work to rethink the violence of quotidian ideology:

precisely because we all think we already know where the trap of ideology lies and hence unconsciously dismiss its force. We therefore succumb to the spectacle of our own cynicism.

Berenice Angremy is a freelance art critic based in Beijing, China. She is also Executive

Director of DIAF, Dashanzi International Art

Festival in Beijing.

=>Back to Great East Asia Co-prosperity Restaurant

=>Great East Asia Co-prosperity Restaurant web in Japanese

=>Back to ARAIart web

ARAI Shin-ichi (web master/shinichiarai@hotmail.com)